Somewhere between personal memory and collective collapse, What Remains is Adel Abidin’s poignant reminder of the scars and debris history leaves behind – even, or especially, as it repeats itself. True to his body of work, the Iraqi visual artist’s exhibition is as deeply political as it is personal. But this time, it’s more subdued and subtle in meaning, messaging, and medium.

It marks Abidin’s return to painting as an intimate, layered, still, and stubborn act of resistance against the speed of the world – inviting us to really sit with displacement, violence and maybe even disillusion. It oscillates between a state of lingering and a moment of reckoning, creating an uneasy space where the past has not yet settled, and the future cannot yet begin. And unlike his previous works where irony and wit prevailed, it is a departure to a more vulnerable place, where silence and slowness carry the weight.

Speaking with ult.society, Abidin reflects on the role of art in resisting erasure, portraying fragments of what’s left and keeping the wound open – with hope defined not as a saving grace for the future, but as the quiet persistence to keep existing in the present.

Curated by Dr. Tamara Chalabi, What Remains is on view at Galerie Tanit Beirut until October 23, 2025.

(Left) Adel Abidin, Drift (triptych), 2025, Acrylic on Canvas, 156 x 600 cm. (Right) Adel Abidin, Displaced, 2025, Acrylic on Canvas, 200 x 310 cm.

Images courtesy of Galerie Tanit Beyrouth/Munich.

What Remains is, true to your craft, deeply political in nature. Can you walk us through the inspiration, process, and timing behind it?

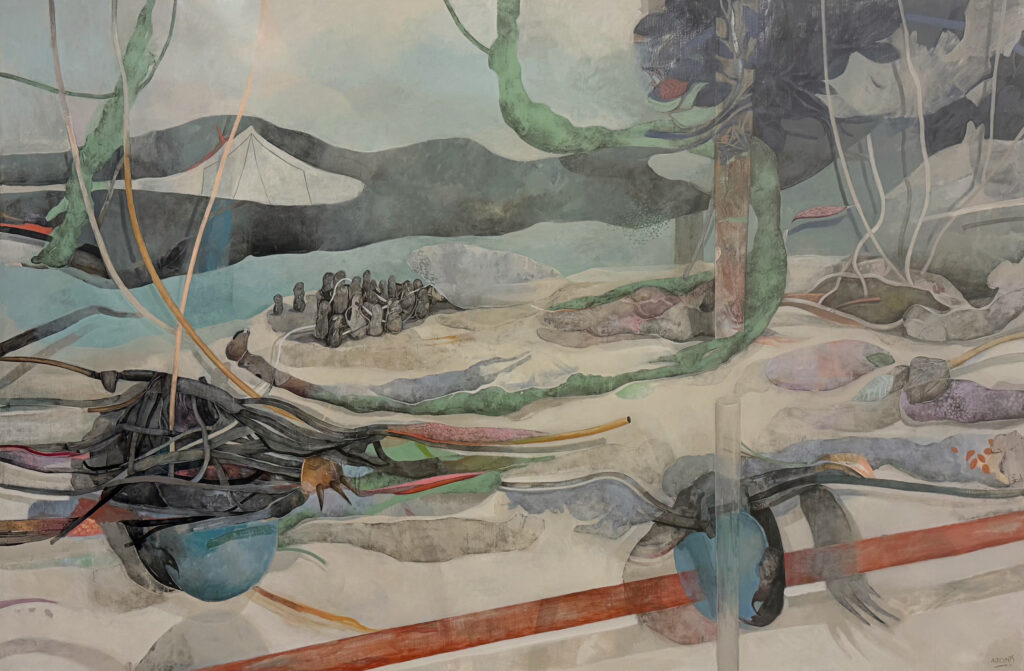

What Remains grew out of a collision between personal memory and collective collapse. I began thinking about how history doesn’t vanish — it survives in fragments, debris, and scars that outlive the moment. The process was less about illustrating events and more about excavating their aftertaste. I wanted the paintings to feel like landscapes and wreckages at the same time – a horizon you can’t quite trust.

I chose to return to painting because I wanted to become intimate with the medium — to use color as a way of layering events and memories. Unlike video or installation, painting let me slow down and embed those layers one over another, almost like sediment, carrying both the visible and the hidden.

The timing came naturally; after years of working with other media, I felt the urgency to embrace painting again, but in a way that holds the same political weight. For me, painting here becomes an act of resistance — slow, heavy, almost stubborn — against the speed of the world we’re witnessing. So the works are political, yes, but not through slogans or direct messages. They’re political because they insist we sit with what’s left behind, to recognize that ruins are also testimonies.

What Remains seems like a rather apt title for the current state of affairs, particularly in our part of the world. But it also suggests something more ambiguous – one might say a quiet, almost fatalist sense of closure. Do you see the exhibition learning toward a resolution, a reckoning, or simply a lingering state?

The title carries all of that tension — it’s not about offering closure or resolution, because I don’t think we’re anywhere near that. For me, it’s about inhabiting the space of what persists. History, violence, displacement don’t have a clean-cut end, they echo. What remains is not just the ruins, but also the memories, the remnants, the unresolved questions.

So the exhibition leans more toward a lingering state, one that resists being packaged neatly. The works hold traces of reckoning, yes, but without pretending to solve or reconcile. I’m more interested in that uneasy in-between — where memory, residue, and desire overlap. That’s where the political charge lies: in confronting the fact that we’re still living among what remains, not beyond it.

Adel, it is not often that you exhibit paintings. What led you back to this medium for your more recent works? What role do you believe this medium played in shaping the context, themes, and message of What Remains in particular?

Coming back to painting wasn’t a nostalgic move. It was a necessity. After years of working with video and installations, I felt the urge to work closer with a medium such as painting that allowed me to slow down and be immersed in it. With painting, I can layer events and memories through color — one layer burying another, yet still seeping through — the way memory itself functions.

This intimacy was crucial for What Remains. The works aren’t illustrations of history, they’re accumulations of traces, echoes, and unresolved fragments. Painting gave me the possibility to hold these contradictions on the same surface: fragility and heaviness, absence and presence, ruin and beauty. In that sense, the medium didn’t just shape the works — it became the message itself, embodying the weight of what endures.

At the end of the day, painting, video, or any other medium are just vehicles to deliver an argument or hypotheses. The technicalities and aesthetics may differ, but the line of thought remains the same. Painting, however, is personal — almost like writing a diary, unveiling my soul, and becoming deeply connected to the canvas I’m working on. For me, painting is an entity with its own soul, and my role as an artist is to search for its code so I can sync myself with its needs.

Adel Abidin, What Remains, Exhibition View, Galerie Tanit, Beirut, 2025.

Images courtesy of Galerie Tanit Beyrouth/Munich

You often use wit, irony and (dark) humor to tackle sensitive and critical topics. But in this exhibition, the tone seems different, perhaps even more restrained. Has your approach evolved, or was it this body of work that demanded this nuanced tone?

I think every body of work dictates its own tone. Humor, irony, and wit have always been my way of opening difficult conversations — to seduce the viewer in before hitting them with the weight of the subject. But What Remains felt different. The themes I’m working with here — memory, loss, residues of history — demanded intimacy rather than distance.

It wasn’t about restraining myself; it was about listening to what the work needed. Humor can disarm, but in this case silence, layering, and slowness carried more power. The paintings called for vulnerability, almost like exposing pages of a diary. So the approach didn’t evolve in the sense of abandoning irony. It expanded, to allow another register of expression – one that’s deeply personal but still political.

How does this exhibition reflect and draw from your personal experience? And how do you reckon it echoes and resonates at a more universal level?

For me, What Remains grows out of fragments of my own story — memories of war, displacement, and the strange silence that follows destruction. These aren’t linear narratives but scattered impressions that stay with me, surfacing like layers of paint where one memory seeps through another. Painting gave me a way to hold them, not to resolve them, but to let them breathe.

At the same time, these traces are not mine alone. They echo across borders and histories. Everyone carries their own ruins — a collapsed city, a fractured home, or an absence that still insists on being present. In that sense, the works move from the personal to the universal. They are intimate, yes, but they also become mirrors for a collective condition: that we are all living among remnants, negotiating what lingers rather than what is complete.

Some would argue that collective memory and identity are at existential stake – in this region as much as in this exhibition. What role do you believe art plays in this context? An anchoring force or perhaps merely a mirror of their erosion?

I don’t see art as either a savior or a passive mirror — it exists somewhere in between. Art can’t stop the erosion of memory or identity, but it can refuse to let them vanish unnoticed. In that sense, it becomes an anchor, not by fixing history in place, but by insisting that its fragments are seen, felt, and carried forward.

For me, art is about creating spaces where memory can linger, even if in fractured form. The paintings in What Remains are not monuments; they are fragile surfaces where traces accumulate, where what’s lost still leaves its mark. Art holds these traces, makes them visible, and in doing so, resists erasure. It doesn’t heal the wound, but it keeps it open. And that, in itself, is a political act.

(Left) Adel Abidin, Above the Abyss, 2025, Acrylic on Canvas, 158 x 170 cm. (Right) Adel Abidin, Metamorphosis, 2025, Acrylic on Canvas, 131 x 145 cm.

Images courtesy of Galerie Tanit Beyrouth/Munich.

Only one of the exhibition’s works, Above the Abyss, seems to convey a sense of optimism, albeit fragile and fleeting. And even that hope is depicted as ‘extraterrestrial’, not belonging to our world. Is this depiction deliberate? How do you see hope in the context of What Remains?

Hope in What Remains is not absent, but it is complicated. In Above the Abyss, it appears almost alien, because in our reality hope often feels like it comes from somewhere else — distant, fragile, not fully grounded. That sense of it being ‘extraterrestrial’ is deliberate; it reflects how survival in the face of collapse sometimes depends on imagining something outside the logic of the present.

But hope here isn’t about resolution or comfort. It’s more like a flicker that interrupts the heaviness of ruins, a reminder that even in devastation, something still insists on existing. For me, that fragile hope is as political as the ruins themselves — not because it saves us, but because it refuses to disappear.

You worked closely with curator Dr. Tamara Chalabi on this exhibition. What kind of dialogue and dynamic emerged between you throughout this collaboration, and how do you believe they shaped the final outcome?

Working with Tamara was not just a curatorial process, but rather an ongoing dialogue. She approached the work with both sensitivity and a sharp critical eye, and that combination created space for trust. Our conversations moved beyond logistics into deeper reflections on history, displacement, and the weight of memory — themes that sit at the core of What Remains.

What I value most is that she never tried to impose a reading. Instead, she opened windows for the work to breathe, helping me sharpen my own language without diluting the ambiguity I wanted to preserve. That dynamic shaped the exhibition into what it became: not a fixed narrative, but a layered conversation between the works, myself, and the world they enter.